Discovering New (and Old) Waterfalls in Georgia

Have you ever wondered how new waterfalls are found and submitted to this database? There are lots of seasoned explorers scouring the North Georgia mountains for undocumented waterfalls all the time. In fact, a significant fraction of the waterfalls on the site have been found in just the last few years. But are all of us just bushwhacking up random creeks, hoping to stumble upon waterfalls? Not quite. The purpose of this page is to describe several tools that will not only make your waterfall excursions more informed, but perhaps even inspire you to go looking for an undocumented waterfall yourself!

UPDATE 7/1/2023: 1-meter LiDAR data is now available for every county in North Georgia!

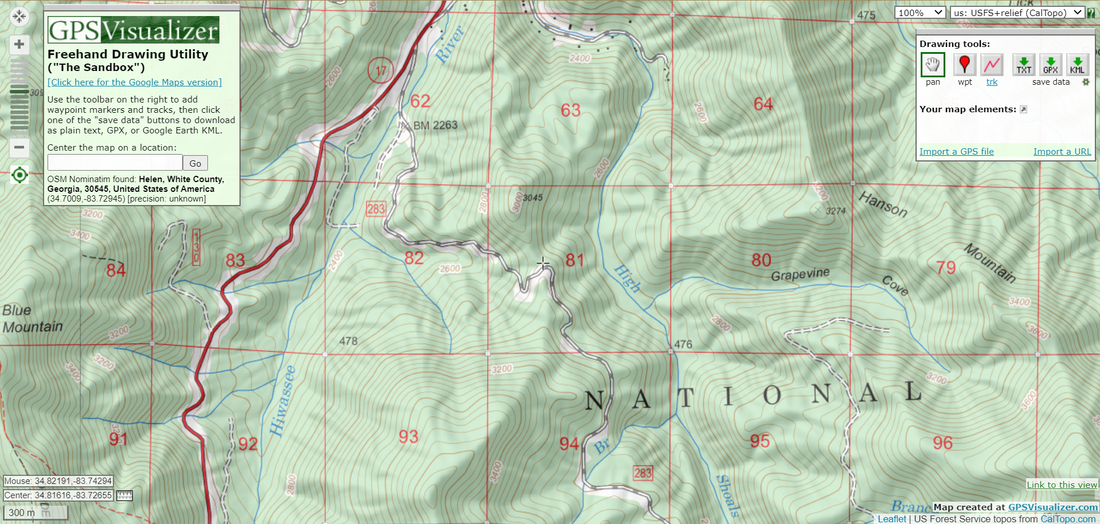

Topo Maps and GPS Visualizer

The basic topographic map has been an essential outdoor exploration tool for generations and remains important today. In a topo map you can find an important overview of any area you're interested in. At the very least, topo maps will typically show names and locations of creeks, mountains, and roads. All drivable forest roads and many gated forest roads will be shown on topo maps. Topo maps can also show some hiking trails and old logging roads, but their locations tend to be less reliable. GPS Visualizer is a website very useful for exploring interactive topo maps digitally. After hitting the "Draw on a Map" tab, you can select from dozens of different map options. For level of detail, my favorites are "USGS + relief" and "USFS + relief", both of which are sourced from CalTopo. GPS Visualizer allows you to draw on maps, mark waypoints, and upload GPS tracks. You can even generate elevation profiles from GPS tracks. GPS Visualizer is my favorite website for exploring topographic maps digitally.

Google Earth

Until very recently, the Google Earth software was the premier technological innovation used by all explorers for identifying waterfalls, documented or not. It remains one of the most useful tools you could find anywhere! Google Earth features 3D satellite imagery of the whole world dating back to 1993, though for us waterfallers, the most recent imagery sets hold the most value. Basically, any area of whitewater that you see on Google Earth is going to be a waterfall. Sometimes Google Earth can be misleading, and the whitewater might turn out to just be a series of steep or dynamic cascades. It is helpful to use the 3D panning feature to gauge the size and steepness of a waterfall (or an area of whitewater).

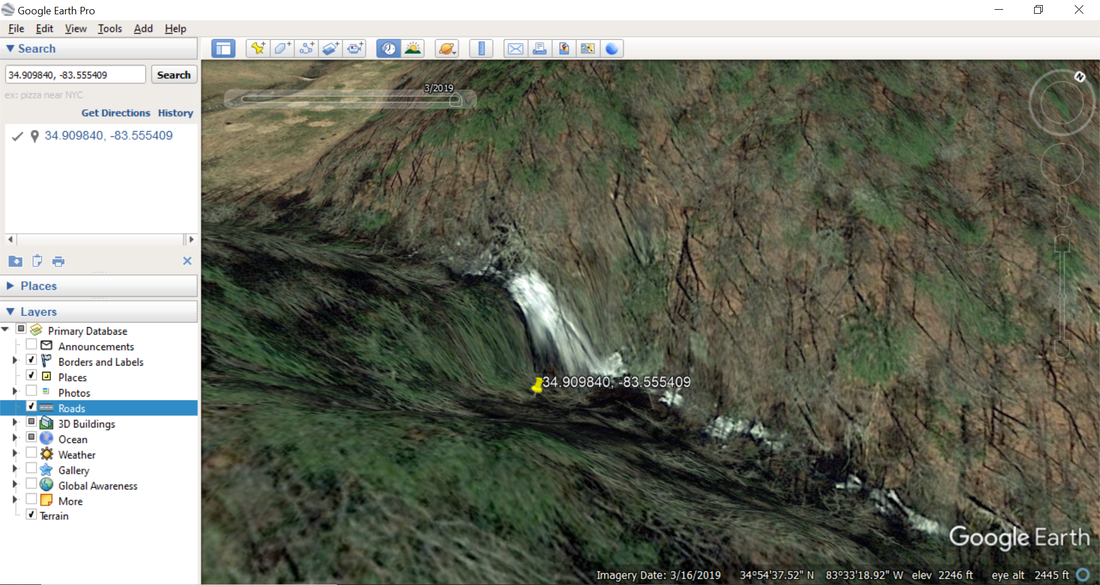

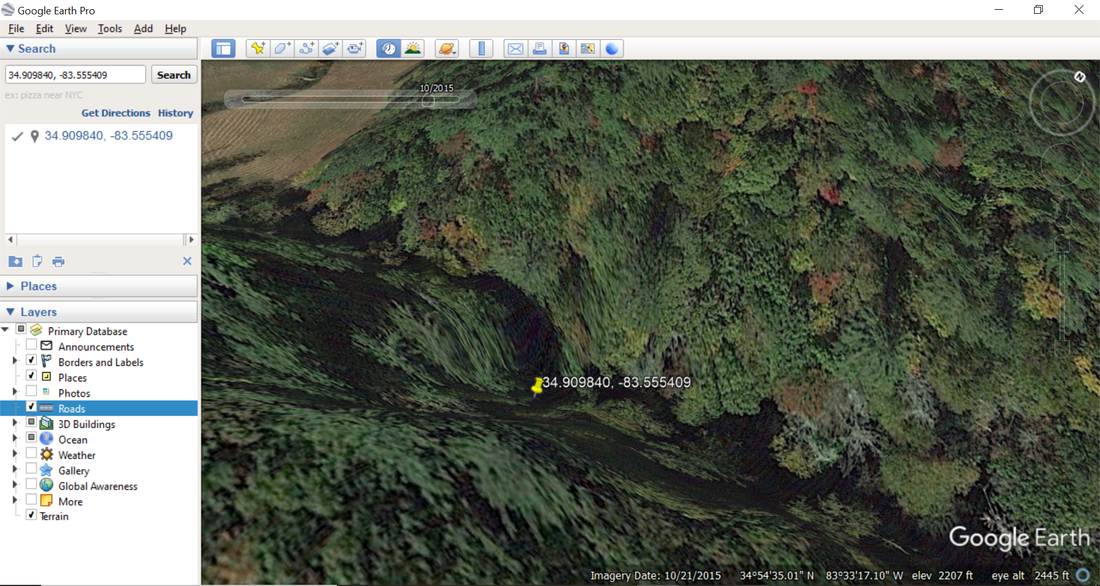

A general rule of thumb is that you need to be looking at a winter or early spring view on Google Earth to see most waterfalls. The waterfalls are usually hidden beneath the forest canopy on satellite imagery where all the leaves are present on trees (such as in mid-summer). The historical imagery slider allows you to navigate between satellite views from different dates. For example, hovering over Angelica Falls in northwest Rabun County, Georgia, the last three satellite views are dated 3/2019, 4/2017, and 10/2015. The 4/2017 and 3/2019 views (screenshot above) are both early spring views, and the trees are bare in these views, so the creek and waterfall are visible well. In contrast, the 10/2015 view (screenshot below) is a fully-forested early fall view, and not one trace of whitewater is visible. Something else to note is the difference in water levels between the 4/2017 and 3/2019 views - the flow is much heavier in the 3/2019 view. Although most waterfalls will be visible in both satellite views, some waterfalls will show up better in higher flow views like the 3/2019 view.

A general rule of thumb is that you need to be looking at a winter or early spring view on Google Earth to see most waterfalls. The waterfalls are usually hidden beneath the forest canopy on satellite imagery where all the leaves are present on trees (such as in mid-summer). The historical imagery slider allows you to navigate between satellite views from different dates. For example, hovering over Angelica Falls in northwest Rabun County, Georgia, the last three satellite views are dated 3/2019, 4/2017, and 10/2015. The 4/2017 and 3/2019 views (screenshot above) are both early spring views, and the trees are bare in these views, so the creek and waterfall are visible well. In contrast, the 10/2015 view (screenshot below) is a fully-forested early fall view, and not one trace of whitewater is visible. Something else to note is the difference in water levels between the 4/2017 and 3/2019 views - the flow is much heavier in the 3/2019 view. Although most waterfalls will be visible in both satellite views, some waterfalls will show up better in higher flow views like the 3/2019 view.

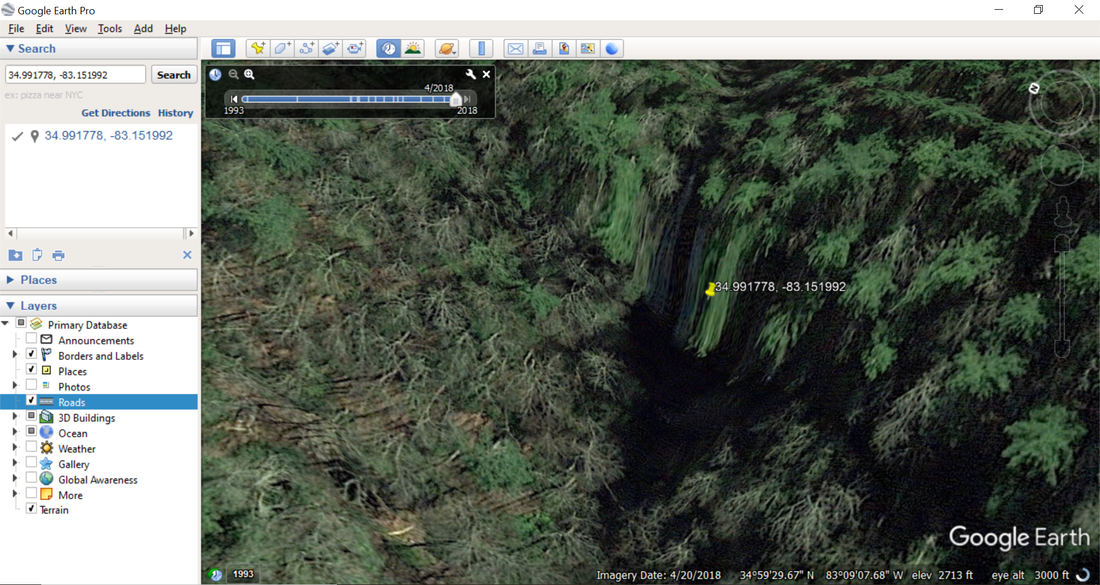

Not all waterfalls will look alike on Google Earth satellite imagery. Some may look like powerful torrents of whitewater, while a thin sliver of white at best may be what you see at others. The Google Earth view below of Hedden Creek Falls in northeast Rabun County, Georgia looks very different from the view of Angelica Falls above. To be fair, this is a 4/2018 satellite view (a 3/2019 view was not available for this area) and the water levels are lower, but there is still a significant difference between how these two waterfalls appear on Google Earth, regardless of water levels.

Therefore, one way I look for undocumented waterfalls is explore creeks for 'unfamiliar' areas of whitewater in places where I'm not aware of known waterfalls. I might first identify an area to look at on a topographic map, place a waypoint in GPS Visualizer, record the GPS coordinates, and paste them into Google Earth. Google Earth is also very useful for me for planning out hikes, beyond just finding waterfalls. I can see forest roads on satellite imagery, so I can figure out where to park. If I'm bushwhacking, I can scan the vegetation on slopes and figure out which areas seem to have more open woods. I can even look for rock outcrops and potential mountain views via Google Earth, though that's beyond the scope of this website. The bottom line is that Google Earth is all around an incredibly valuable and indispensable tool for waterfall hunters. Click here to access the page where you can download Google Earth. Note that Google has recently released a web version of Google Earth, but I still prefer using the traditional Google Earth Pro for desktop. Also note that the satellite imagery in Google Earth Pro is much more detailed than the aerial imagery views on Google Maps (I often haven't been able to identify waterfalls on Google Maps aerial imagery that I were well-defined in Google Earth).

Therefore, one way I look for undocumented waterfalls is explore creeks for 'unfamiliar' areas of whitewater in places where I'm not aware of known waterfalls. I might first identify an area to look at on a topographic map, place a waypoint in GPS Visualizer, record the GPS coordinates, and paste them into Google Earth. Google Earth is also very useful for me for planning out hikes, beyond just finding waterfalls. I can see forest roads on satellite imagery, so I can figure out where to park. If I'm bushwhacking, I can scan the vegetation on slopes and figure out which areas seem to have more open woods. I can even look for rock outcrops and potential mountain views via Google Earth, though that's beyond the scope of this website. The bottom line is that Google Earth is all around an incredibly valuable and indispensable tool for waterfall hunters. Click here to access the page where you can download Google Earth. Note that Google has recently released a web version of Google Earth, but I still prefer using the traditional Google Earth Pro for desktop. Also note that the satellite imagery in Google Earth Pro is much more detailed than the aerial imagery views on Google Maps (I often haven't been able to identify waterfalls on Google Maps aerial imagery that I were well-defined in Google Earth).

LiDAR

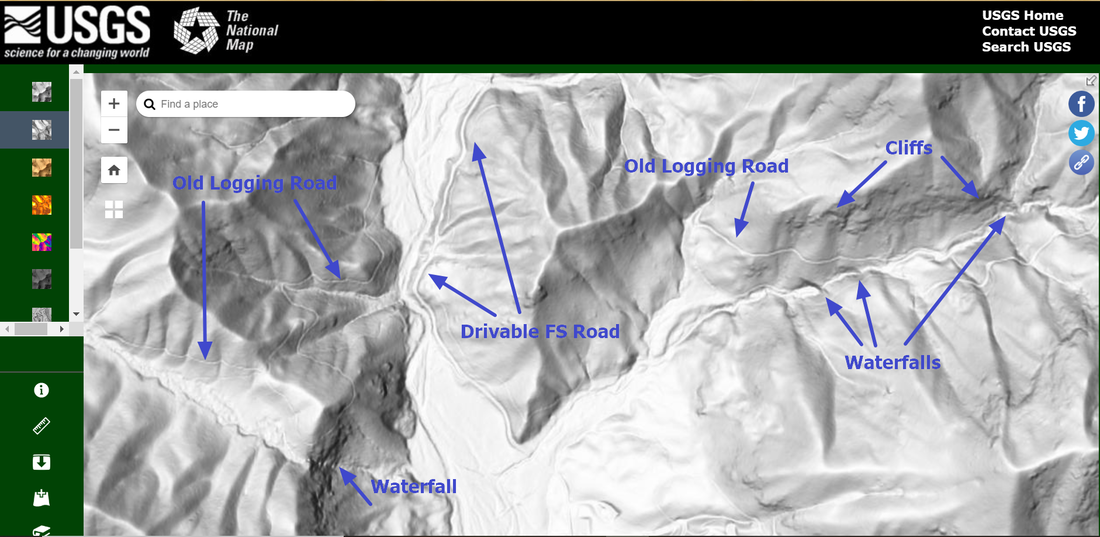

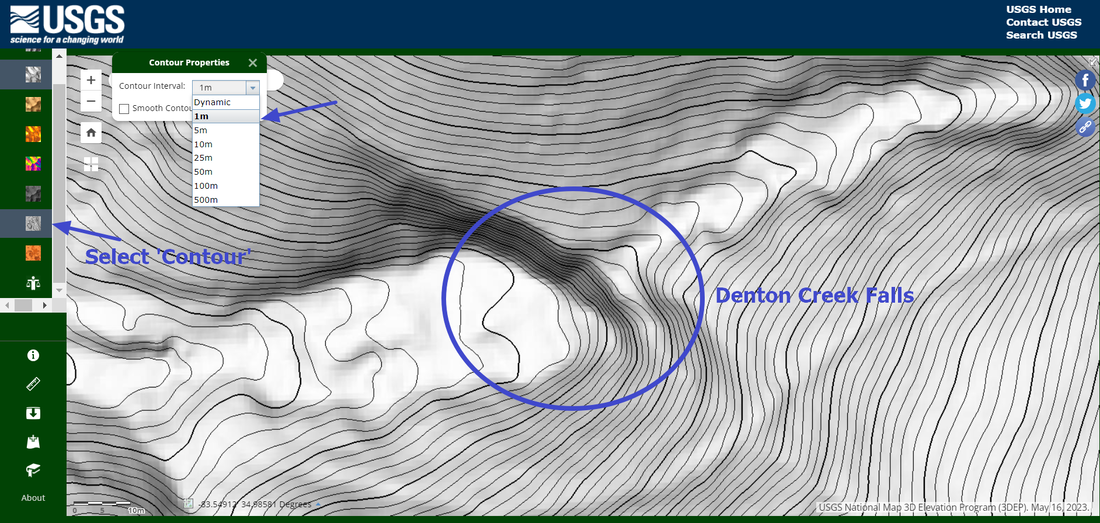

LiDAR. Light Detection and Ranging. This new innovation is the granddaddy of all waterfall hunting tools. Basically, if LiDAR data is available for a region, you'll be able to locate any and every waterfall that exists. Documented or undocumented. Whether it's 100 feet high or 5 feet high. Almost sounds too good to be true, right? Defined literally, LiDAR is a method of measuring distances via laser lights pointed down from aircraft. LiDAR data comes in many different forms with numerous applications, but us deranged waterfallers are primarily interested in two versions of this data: hillshade and 1-meter contour. I'm going to discuss hillshade first, as I find it to be the more useful of the two. Follow along with me by clicking here to open the interactive USGS 3DEP Explorer website, which houses a lot of LiDAR data.

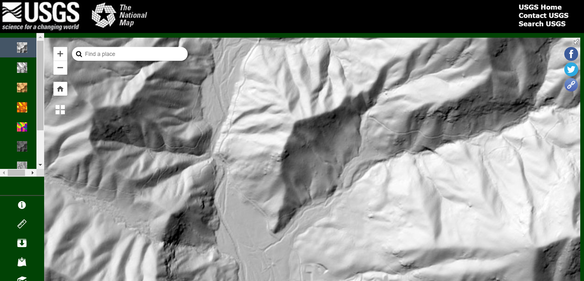

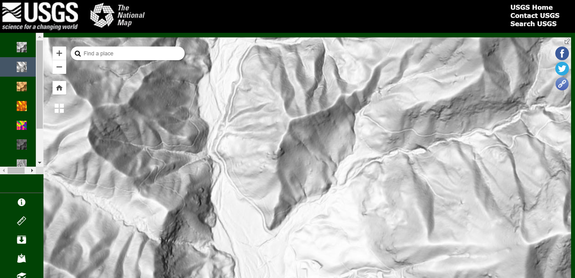

When you first open the website, by default, you'll be on the hillshade map view (if you turn it off in the sidebar on the left, you'll be looking at a regular topo map). I prefer using multi-directional hillshade rather than regular hillshade. This is because regular hillshade analyzes terrain from one specific angle, so some slopes like north-facing slopes will have less detail than others. Multi-directional hillshade combines data collected from several different angles, making it harder to miss important details (see the comparison below).

Whenever you're looking at a creek on hillshade, any waterfall will show up as an abrupt dark area. A dark 'line' on hillshade indicates a cliff, and waterfalls occur where cliffs are! Darker lines at creeks often indicate steeper and larger waterfalls (more sheer cliffs), though the shades of gray and black also depend on which direction the slope is facing. Hillshade also shows the paths of many abandoned old logging roads, since these old roads were carved out of the hillside and are usually noticeable indents. In addition, hillshade is very useful for planning out cross-country off-trail hikes, since it can show the locations of cliffs that you have to avoid.

There are a couple things you have to keep in mind as you use hillshade to look for waterfalls. The different shades of gray can be a bit deceiving. While hillshade will show absolutely every waterfall that exists, it can also suggest that waterfalls exist in places where they don't (it could just be something like a steep, overgrown cascade). Also, logging roads that show up very well-defined on hillshade can in reality turn out overgrown or even impassable. That is just the unpredictable nature of off-trail exploration. Tools like LiDAR make planning easier, but surprises are inevitable.

Now let's talk about 1-meter contours. LiDAR is unique in the fact that it is essentially a topo map on steroids. Topographic maps typically contain contours at 40-foot or 20-foot intervals. But using LiDAR, you can see a topo map with 3-foot contour intervals! Using 3-foot contour intervals, you can estimate the height and steepness of any waterfall. Suppose you were exploring hillshade and think you might have found a waterfall. You can use the 1-meter contours to help figure out if this is actually a waterfall or just a cascade. Of course, neither hillshade nor 1-meter contours will tell you how overgrown a waterfall is, but Google Earth can be helpful in this regard. The significant advantage of LiDAR over Google Earth is that many waterfalls in more forested areas and on smaller streams will simply not show up through the trees on Google Earth satellite imagery - while on LiDAR, every single waterfall shows up.

There are a couple things you have to keep in mind as you use hillshade to look for waterfalls. The different shades of gray can be a bit deceiving. While hillshade will show absolutely every waterfall that exists, it can also suggest that waterfalls exist in places where they don't (it could just be something like a steep, overgrown cascade). Also, logging roads that show up very well-defined on hillshade can in reality turn out overgrown or even impassable. That is just the unpredictable nature of off-trail exploration. Tools like LiDAR make planning easier, but surprises are inevitable.

Now let's talk about 1-meter contours. LiDAR is unique in the fact that it is essentially a topo map on steroids. Topographic maps typically contain contours at 40-foot or 20-foot intervals. But using LiDAR, you can see a topo map with 3-foot contour intervals! Using 3-foot contour intervals, you can estimate the height and steepness of any waterfall. Suppose you were exploring hillshade and think you might have found a waterfall. You can use the 1-meter contours to help figure out if this is actually a waterfall or just a cascade. Of course, neither hillshade nor 1-meter contours will tell you how overgrown a waterfall is, but Google Earth can be helpful in this regard. The significant advantage of LiDAR over Google Earth is that many waterfalls in more forested areas and on smaller streams will simply not show up through the trees on Google Earth satellite imagery - while on LiDAR, every single waterfall shows up.

LiDAR has become a very controversial subject in the hiking community. While more and more people are discovering it as a brilliant new invention for exploring the mountains and finding waterfalls, others have taken the stance that LiDAR is a "cheat". Those latter people prefer to stick to older-school tools like Google Earth or even just plain topographic maps. My personal position is that I will take advantage of any tools that will make planning out my waterfall explorations/visits easier, safer, and more fun. I am sharing all of this information about LiDAR to help improve waterfall exploration experiences for others too, because LiDAR is not common knowledge yet, and I don't believe that it is right for me to hoard this knowledge. With that said, if you do not want to use LiDAR because you think it is a cheat, this is entirely your prerogative and you can ignore the information that I have provided here.

Previously, LiDAR data was only available for select counties in northeast Georgia. From personal experience, I have confirmed that, as of July 2023, accurate hi-res LiDAR data is now available for all North Georgia counties. I also know that LiDAR data is available for select counties throughout the rest of Georgia such as Fulton County and Upson County, but I haven't checked if it is available for every county in the state. I anticipate that LiDAR coverage will become more widespread across Georgia over time as additional funding is secured, but there's no telling how long this will take.

Let me add one other note to dispel any confusion about sources for LiDAR data. For Georgia, the USGS 3DEP explorer website is the only current public source of LiDAR data that I am aware of. The USGS website is also a great place to explore LiDAR data for other regions across the United States. With that said, some states like Tennessee and South Carolina have published online more detailed downloadable LiDAR data files. You would need to invest some time in using a software like QGIS to unlock data like hillshade and contour for these files. The files are also huge in size, requiring a high-speed internet connection and ample hard drive space to download and open. I have generally preferred to explore LiDAR using the USGS website due to its user-friendly interface and ease of access. I have enough QGIS knowledge to explain how to open LiDAR files that way too, but all of this is irrelevant to Georgia, since I have never run across any downloadable LiDAR files for Georgia.

Previously, LiDAR data was only available for select counties in northeast Georgia. From personal experience, I have confirmed that, as of July 2023, accurate hi-res LiDAR data is now available for all North Georgia counties. I also know that LiDAR data is available for select counties throughout the rest of Georgia such as Fulton County and Upson County, but I haven't checked if it is available for every county in the state. I anticipate that LiDAR coverage will become more widespread across Georgia over time as additional funding is secured, but there's no telling how long this will take.

Let me add one other note to dispel any confusion about sources for LiDAR data. For Georgia, the USGS 3DEP explorer website is the only current public source of LiDAR data that I am aware of. The USGS website is also a great place to explore LiDAR data for other regions across the United States. With that said, some states like Tennessee and South Carolina have published online more detailed downloadable LiDAR data files. You would need to invest some time in using a software like QGIS to unlock data like hillshade and contour for these files. The files are also huge in size, requiring a high-speed internet connection and ample hard drive space to download and open. I have generally preferred to explore LiDAR using the USGS website due to its user-friendly interface and ease of access. I have enough QGIS knowledge to explain how to open LiDAR files that way too, but all of this is irrelevant to Georgia, since I have never run across any downloadable LiDAR files for Georgia.

First in Georgia!

Get Mark's brand new

guidebook to 700+ falls.